Though my primary field is Tudor-Stuart history, occasionally I teach a more general English history survey which spans from Roman era to the seventeenth century. My biggest challenge in this course, which I am teaching this semester, is to refrain from settling into mere storytelling about the characters and exploits of a succession of colorful kings and queens. The students in this course are generally not history majors, and their knowledge and interest in history tends to be quite History Channel-ish, meaning that they are more interested in personalities than structures. I try to balance it all out, and for the most part I think I’m successful, but periodically I must slow down and simply consider the character and reign of a monarch in rather narrative fashion. Such is the case with King Henry II, nicknamed Curtmantle for the shorter French/Angevin mantle he supposedly wore, who was born on this day in 1133. It doesn’t matter how much I dwell on King Henry–they want more, and I’m wondering why? Of course the broad strokes and details of his life are dramatic–the rise to power in the wake of Civil War, his conquest and contests with Queen Eleanor, his family fights, his multi-front wars, the murder of Archbishop Becket in Canterbury Cathedral and the penitential consequences–I still think that it’s the popular characterization of Henry rather than the historical one that has captivated my students. Even though they’re far too young to remember Peter O’Toole in Becket (1964) and The Lion in Winter (1968), he is still their Henry.

Peter O’ Toole in a publicity photograph for Becket (1964) and a still from The Lion in Winter (1968).

My students are so young they haven’t even seen or heard of O’Toole’s portrayal of Henry II, but when I ask them what they know about him, they describe O’Toole’s portrayal: now that’s a powerful performance! Once again, we see that history is produced by film (sigh). But I think you have to go further back: not (of course) to the actual era of Henry II, but to that which produced the characterization that inspired O’Toole’s performance. Henry became Henry because of his hand in martyring Becket, of course, but also because of his women: his wife Eleanor and his mistress Rosamund Clifford, the “fair Rosamund”. Henry’s struggles with the Church in general and Becket in particular appealed to 18th and 19th historians charting secular “liberation”, while their more romantic counterparts in the arts focused on the women: the Pre-Raphaelites in particular seem to have been obsessed with Eleanor and particularly Rosamund, featuring them both individually and together in mythical contest (based on an old fable alleging the Queen tried to poison the mistress). This is all very dramatic stuff, almost equaling the narrative of that dynasty of the (long) moment, the Tudors. I predict a Plantagenet comeback.

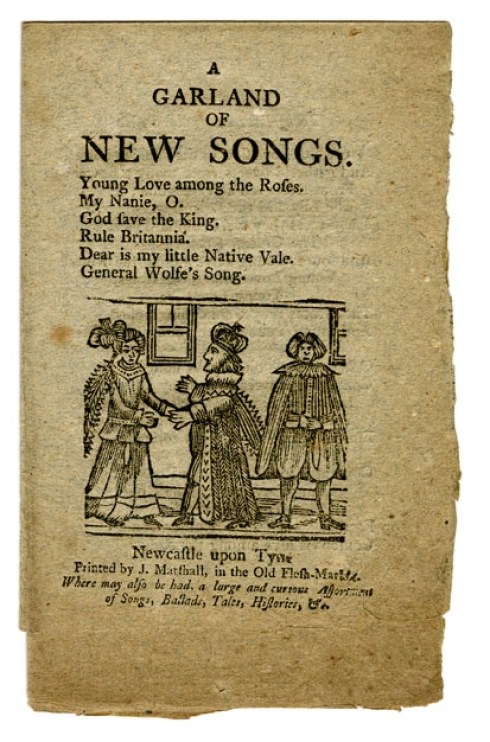

Henry II as characterized by Alfred Crowquill’s Comic History of the Kings and Queens of England (Read & Co, c 1860) and Rosalind Thornycroft in Herbert and Eleanor Farjeon’s Kings and Queens (1932). A chapbook of folk ballads with Henry II and the Fair Rosamund on the title page, c. 1815-30, British Museum; Queen Eleanor and Fair Rosamund by Evelyn de Morgan, 1905, De Morgan Centre, London;The Fair Rosamund by John William Waterhouse, 1916, National Museum Wales.

March 5th, 2015 at 8:56 am

A huge part of the attraction in studying Henry II must also lie in those gripping contemporary or near-contemporary accounts of the slaying of Thomas a Beckett. One was even an eye witness I believe, which adds further power to the story.

March 5th, 2015 at 8:59 am

Oh no question, Alastair. And the imagery–centuries worth–of both the murder in the Cathedral and Henry’s penance. It’s funny how the romantic stuff overwhelms Becket in the 19th century though…..

March 5th, 2015 at 11:37 am

I too love the story telling.. story telling is ancient too.. c

March 5th, 2015 at 6:24 pm

Katherine Hepburn must play an important role here too – her portrayal of Eleanor in The Lion In Winter is fabulous. And Eleanor IS fabulous, whichever way you parse her – heiress, divorcee, Queen of two kingdoms, crusader, prisoner, and a walk on part in the 1950s BBC production of Robin Hood. What’s not to like!

March 5th, 2015 at 6:30 pm

She’s definitely a big part of the Henry II history and mythology, although I must admit Hepburn bothers me a bit in the film–she’s so theatrical! But I guess the whole move is pretty theatrical.

March 5th, 2015 at 6:40 pm

Yes, it’s adapted from a stage play, and still has a claustrophobic feel to it, all talk and very little outside action.

March 5th, 2015 at 6:45 pm

Exactly. Lots of (anachronistic) speeches, But still great, in its way.

March 7th, 2015 at 3:48 am

Reblogged this on Progressive Rubber Boots.