There are many people who have contributed to the creation and projection of Salem’s image over the last century and more, beginning with the rather solemn portrayals of Nathaniel Hawthorne and proceeding through the material-based photographs and writings of Frank Cousins and Mary Harrod Northend towards the Witch City profiteers of our own time. But perhaps no one was more avid and energetic in these efforts than George Francis Dow (1868-1936), a prolific author and editor, secretary of the Essex Institute (now absorbed into the Peabody Essex Museum), director of the museum of the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities (now Historic New England), and the principal force behind Salem’s recreated colonial settlement, Pioneer Village. It’s difficult to categorize Dow: he was not a trained historian but this was no obstacle to his efforts and achievements. Generally he is referred to as an antiquarian, which is a rather antiquated word now. He certainly possessed the technical expertise of a preservationist. Above all, I think, he was an interpreter and an admirer of the colonial past. When he was 30 years old, he simply quit his job at a wholesale metal company in Boston and began to indulge his passion for the colonial history of Essex County full-time, with rather impressive results: a succession of books (The Sailing Ships of New England, Whale Ships and Whaling, The Arts and Crafts of New England, Every Day Life in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, just to name a few titles), the installation of pioneering period rooms at the Essex Institute, the relocation and restoration of the seventeenth-century John Ward House, and “Salem in 163o: Pioneer Village”, erected for the 300th anniversary of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. In 1920 (at the age of 52) he married Alice G. Waters, one of the co-editors of his four-volume edition of The Diary of William Bentley and a long-time librarian at the Essex Institute (so romantic!).

I often think about Dow when I come across one of his books, but most especially whenever I go to Pioneer Village, which still survives as America’s first living history museum, predating Colonial Williamsburg by several years. The village was meant to be a temporary installation for the Tercentenary celebration but Dow and his associates (principally architect Joseph Everett Chandler) put so much effort and thought into its design and construction that it remained a tourist attraction well into the 1950s. Shuttered for several decades thereafter, it deteriorated precipitously, but was restored in several sequences by devoted Salem museum professionals in the later 1980s and after 2007. This past weekend, I went to the village for the first-ever “Salem Spice Festival” and began thinking about Dow’s work–and vision–again. The village is much changed from its original appearance, as will be immediately obvious by the contrasting photographs below. But it’s all in the details: in several structures the colonial craftsmanship which Dow so admired and strove to recreate is still in evidence, almost 85 years later.

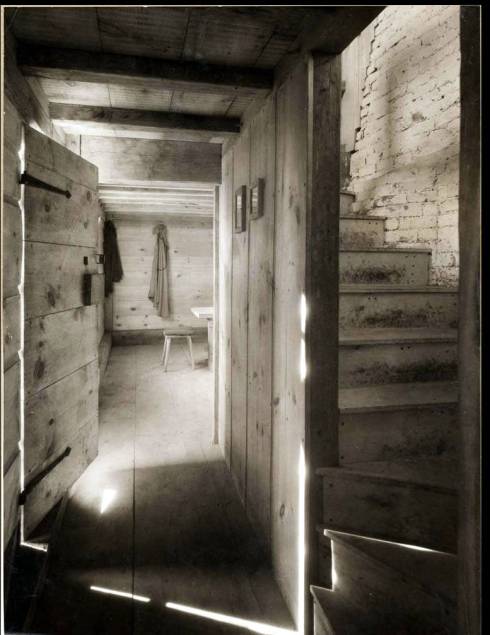

Pioneer Village, Forest River Park, Salem in the 1930s and today, including the Governor’s “Fayre” House interiors: period photographs from the Ryerson & Burnham Archives Archival Image Collection at the Art Institute of Chicago (several of which were used in Dow’s Every Day Life in the Massachusetts Bay Colony). Dow’s narrative of Pioneer Village can be found in the journal he edited for the Society of New England Antiquities: “Old-Time New England”,”A QUARTERLY MAGAZINE DEVOTED TO THE ANCIENT BUILDINGS, HOUSEHOLD FURNISHINGS, DOMESTIC ARTS, MANNERS AND CUSTOMS, AND MINOR ANTIQUITIES OF THE NEW ENGLAND PEOPLE”; Volume XXII; JULY, 1931; Number I. Sadly, the reproduction Arbella, which carried John Winthrop’s expedition to “Salem 1630”, has not survived, but Leslie Jones captured it in all its glory for the Boston Globe in 1930.

September 17th, 2014 at 1:08 pm

I’ve always been fascinated by Dow. One doesn’t see that sort of amateur much anymore. I suppose that the village is impossibly romanticized, but really that is part of the point, isn’t it?

I think Olde Salem shares honors with Storrowtown Village as the first living history village–Storrowtown was begun in 1927, completed in 1931.

September 17th, 2014 at 7:05 pm

I know; I’m interested in the power of the passionate amateur– you certainly don’t see that type of impact anymore; unless there is money involved. I stand corrected re Storrowtown!