I wanted to follow up my Post Office post with one featuring the art of letters, but I’m not sure exactly how to categorize these images: these are not examples of typographic art, as they feature script rather than print, or ephemeral art, because I’m including works of art which feature letters as well as a few letters that I believe rise to an artistic level. I looked up “scriptural art”, but that category seems to be reserved for religious works, and scribal art for calligraphy. So that leaves me with the rather bland title “the art of letters”.*** It happens that some of my favorite images have a focus on reading or writing letters, or present an assemblage of writing materials, or a scrap of paper, with writing, that makes us wonder what’s going on here? what does that letter say? The letter is a great device to draw us into the painting: we want to read it! Look at the note in the hand of this Victorian governess in Richard Redgrave’s 1844 painting: it–or rather her reaction to its contents–has separated her from the “lighter” children under her watch. The painting was exhibited with the quotation “She sees no kind domestic visage here”, indicating that the letter brought memories of a missed home at best, and news of a death in her family at worst.

Richard Redgrave, The Governess (1844), Victoria & Albert Museum, London

My very favorite letter painting doesn’t really delve into the emotional aspects of letters and their reception, but rather it presents us with a trompe l’oeil display of printed and writing materials: an early modern bulletin board! This is a very ephemeral painting in several ways: the newspapers and almanac represent the “news” of Queen Anne’s accession in 1702, as does the medal representing her grandfather, Charles I. The painter has included his “signature” on the folded sheet in the center. I love trompe l’oeil in general, but this particular painting has captivated me since the first time I laid eyes on it several years ago; I think that George Tooker’s 1953 painting, The Letter Box, is its perfect companion piece.

Edward Collier (Collyer), Trompe L’Oeil with Writing Materials, c. 1702, Victoria & Albert Museum, London; George Tooker, The Letter Box, 1953, Hirshorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C.

Moving back to my period, I noticed a while ago that the Tudor court painter Hans Holbein the Younger often included scraps of paper with writing, tucked into a book, laying on a table, or even posted to the wall, in a number of his portraits. The well-known portrait of Thomas Cromwell (of whom I am a fan) is a good example, as is the amazing portrait of Georg Gisze, a German merchant stationed in London (like Holbein). I think the use of written and writing materials is a bit more straightforward here: Cromwell wants to present himself as a pious public servant and a master of the (written) law, while Gisze is an equally-earnest man of business who holds in his hand a letter from his brother, back home.

Hans Holbein the Younger, Portrait of Thomas Cromwell, 1532-33, Frick Museum; and Portrait of Georg Gisze, 1532, Staatliche Museen, Berlin.

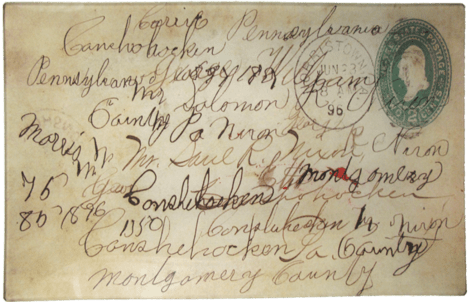

I’m including a few actual letters in this post, both because I spent quite a bit of time searching through the digital collection of the National Postal Museum at the Smithsonian for my last post and because many of the letter “covers” in this collection do rise to the level of art, in my humble opinion. The range is incredible, encompassing patriotic examples from all the American wars, letters from the prisoners of those wars which were delivered in specially-marked envelopes, and letters delivered by planes, trains, and zeppelins. These covers are also a way to look at print and script together. This first envelope, from my own collection, was issued by the Locke Regulator Company of Salem in 1899 (as you can see by the postmark), and then there’s a letter from a Union prisoner of war from 1864 and a letter carried out of Paris by balloon in 1871.

Covers from 1864 & 1871, National Postal Museum, Smithsonian Institution.

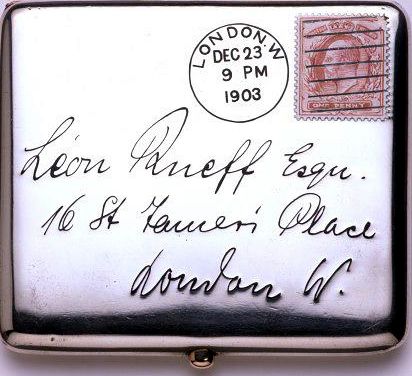

These letters look like likely candidates for a John Derian decoupage tray to me: that man loves his fonts and scripts! But letters moved to the foreground in the decorative arts a while ago, as exemplified by the beautiful silver cigarette case below, “postmarked” in 1903. I wish we could bring these cases back (with an alternative use), and while we’re at it, letters too!

John Derian “Sample Script” decoupage tray; Silver cigarette case by Albert Barker, Ltd., London, Collection of the Victoria & Albert Museum.

***EPISTOLARY Art!!! As recommended by Secret Gardener, who has one of the most beautiful blogs out there.

March 14th, 2013 at 7:13 am

If you haven’t already read it, I highly recommend:

Handwriting in America: A Cultural History

by Tamara Plakins Thornton.

Her extensive discussion of different handwriting styles for different purposes/occupations is fascinating!

March 14th, 2013 at 7:27 am

I haven’t, Priscilla: will put it on my list. I’ve read several books on scribal culture in Europe, but as you know, I’ve got a lot to learn about American history. This book looks great, thanks.

March 14th, 2013 at 7:32 am

The category wouldn’t be ‘epistolary’ ?

March 14th, 2013 at 7:40 am

Oh I like that–epistolary art! Thanks.

March 14th, 2013 at 7:33 am

Letters. Good follow up. I remember getting letters from my Grandparents as a boy. And writing girls from summer camp and getting letters back from them. Even when I was in the Navy, letters were important.

I remember the feeling, when you open the mailbox and see a letter for you, from someone you really want to get a letter from.

And you can feel love in their handwriting.

March 14th, 2013 at 7:54 am

Oh yes, Mark – I, too, remember letters as an important part of my life: letters from grandparents and from a favorite aunt, letters to and from camp friends during the year, and school friends when I was at camp, thank you letters for gifts and kindnesses received. And then when I had children of my own and remembered how important it was to get mail when I was away from home, I wrote daily letters to them at camp – including a card or letter that we actually mailed on the way home from dropping them off, just so they’d have a letter at the first mail call!

And I recently attended a conference co-sponsored by ancestry.com and the New England Historical Genealogy Society, at which all the latest technology was discussed in terms of usefulness to genealogists – and then we were all encouraged to publish our own research in paper form (anywhere from a few typed pages to a fully bound book) in order for future generations to be able to benefit from our findings. Technology changes so rapidly that today’s cutting edge may be completely unusable in a generation or two – remember phonograph cylinders? Wire recordings? Floppy disks? Even if the media don’t become corrupted or otherwise unreadable, our descendants may not have access to devices to unlock their secrets. But written words are still the best way to preserve information for posterity.

And as you point out, Mark, we can actually feel the love in handwriting. One of my greatest treasures is a letter from my grandmother to my grandfather before they were married. I feel so close to my mother’s mother (who was born 125 years ago this month) when I look at her writing and read her words.

And Donna, you have clearly touched a chord with this topic!!!

March 14th, 2013 at 1:04 pm

I agree, all the data on computers and the internet is all 1’s and 0’s on some magnetic material. To me, it’s not really tangible or real as writing on paper or in a book.

March 14th, 2013 at 8:48 am

As an erstwhile letter-writer, I love this post.

Secret Gardener’s suggestion of the term “epistolary” is spot on – in other art forms, you get epistolary novels and epistolary plays. In visual art, letters as subject matter create the class of “epistolary paintings” or “pictures.” They became very popular in the 18th century concurrently with the novel form of storytelling through letters and the development of impressive mail systems. Art historian Nina Dubin has worked on this topic a lot.

http://art.gwu.edu/news_events/VS_13_2_20_Dubin.php

March 14th, 2013 at 10:59 am

Thanks! Great comments today; I am learning a lot.

March 14th, 2013 at 10:00 am

Interesting, serendipitiously I am re reading ‘The Post Office’ by Charles Bukowski – illuminating about the plight of a mail carrier, and a wonderful presentation of the human condition under workhouse conditions! Also, I have recently made my header from a similar trompe l’oeil!

March 14th, 2013 at 11:19 am

It’s very similar! Love it.

March 15th, 2013 at 2:42 pm

I have always been interested about what letters mean. More specifically, what one’s penmanship says about the person who wrote it! It’s so personal. This is a link to late-medieval “postcard” … I can’t date it specifically or even say what language it is, but it is so fascinating!! http://artsonline.monash.edu.au/research-showcase/files/2013/01/CP140194701.jpg

March 16th, 2013 at 2:02 pm

Great selection of images. I too am partial to Collier’s trompe l’oeil and Dror Wahrman’s work on this is fascinating. I had a chance to hear a talk by him a couple of years ago and I was enthralled. He’s just published a book on it…

Mr. Collier’s Letter Racks: A Tale of Art and Illusion at the Threshold of the Modern Information Age (OUP, 2012)

March 16th, 2013 at 2:37 pm

Thank you so much for the reference, Brodie: I’m heading right over to Amazon!

April 7th, 2013 at 10:02 am

[…] Streets of Salem. Beautiful . . . just beautiful. […]