I’m back at school for the Spring semester with the typical four-course teaching load, including a modern world history course that I have not taught for some time. So it is time to refresh my arsenal of Powerpoint presentations and maps. An interesting map can quickly catch a college student’s attention as easily as it does a blog reader, and after perusing my various digital collections a bit, I realized that I might be able to teach world history almost exclusively through octopus maps! Or at least nineteenth- and twentieth-century history: the creature does not seem to have been used as a metaphorical device before 1870. I searched in vain for a map or caricature depicting Napoleon as an octopus but could not find one, which is incredulous: few rulers deserve an octopus map to represent their regimes more than the little Corsican! There’s nothing too terribly original about this post: octopus maps have captured the attention of several bloggers before me (also see here), but I can’t resist putting my own take out there.

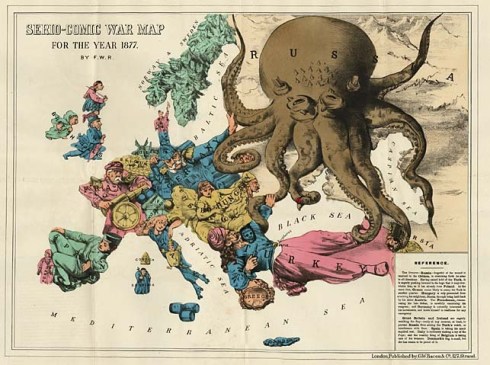

1870 marks a turning point in European and world history with the unification of Germany (as well as Italy): Europe was now “filled out” and further territorial ambitions could only be satisfied by global imperialism and/or war. The maps from this time forward reflect this jingoism and fear, but anthropomorphic satire dulls the edge. One of the first major octopus maps, Fred Rose’s “Serio-Comic War Map For The Year 1877” shows Russia as the octopus-aggressor rather than Germany, even though the Crimean War had revealed the severe weaknesses of the Russian Empire (this is reflected on the map below by wound on one of the octopus’ tentacles–that which is located in the proximity of the Crimea). From the British perspective that this map represents, it’s a bit early to portray Germany as the aggressor, and so Russia becomes either the ferocious bear or the reaching octopus.

F.W. Rose, “A Serio-Comic Map of the Year 1877”, London: G.W. Bacon & Co., British Library; (an earlier Dutch map at the University of Amsterdam upon which this map is based is identical except for the wounded tentacle).

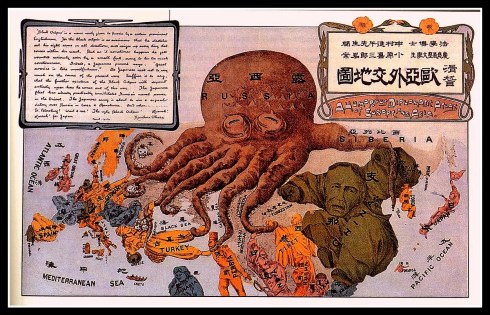

A later Rose map, even more obviously depicting the British perspective, is “John Bull and his Friends” from 1900 in which John Bull (Great Britain) faces a continent full of hostile, disinterested, or preoccupied “friends” and an even more threatening octopus-Russia, reaching out in all directions. On the eve of the Russo-Japanese War (1904-5), a Japanese take on the Serio-Comic map shifts the focus decidedly eastward and portrays Russia as the “black octopus”. And for a completely contrary view, a Japanese print self-identifies with the octopus after the war commenced with the Battle of Port Arthur.

F.W. Rose, “John Bull and his Friends: a Serio-Comic Map of Europe”, London: G.W. Bacon & Co., 1900; K. Ohara, “A Humorous Diplomatic Atlas of Europe and Asia”, 1904; “Tako no asirai”, The Japanese Octopus of Port Arthur, 1904, Library of Congress.

In addition to aggression and domination, whether threatened or realized, the octopus is just the perfect symbol, visual metaphor, avatar of imperialism, and the period between 1870 and 1914 was the golden age of the “new” imperialism, in which Europeans divided up the world, eager to get their piece before Britain gobbled it all up. Consequently there are probably more images portraying John Bull as the octopus rather than John Bull confronting the octopus, like this famous American cartoon, which was published in Punch in 1882.

Anonymous American cartoon, “The Devilfish in Egyptian Waters”, 1882: John Bull makes a grab for Egypt, initiating the “Scramble for Africa”.

The octopus was not just used externally to criticize an opposing or competitive nation’s policies but also internally on a partisan basis, particularly in America and Britain. This particular sea creature can symbolize greed just as well as territorial expansion, and this was a gilded age as well as an age of imperialism. Consequently we see octopuses portraying greedy capitalistic monopolists and associated special interests, on both sides of the Atlantic. In America, Puck magazine illustrator Udo Keppler used the octopus to characterize Standard Oil in 1904 and President Wilson’s fight for “business freedom” a decade later, while in Britain its use was more literally land-based: as a Socialist critique of urban “landlordism” around London just prior to World War I, and to depict urban sprawl from a traditional planning perspective.

Udo Keppler octopus illustrations for Puck magazine, 1904 & 1914, Library of Congress; W. B. Northrup’s “Landlordism” postcard and book cover of Clough Williams-Ellis’s England and the Octopus (1928), British Library.

As the octopus was a well-recognized symbol of aggression by the time that World War I broke out, it was only natural that it would appear on several anti-Germany maps. The English and French maps below, from 1915 and 1917 respectively, both single out Prussian aggression, an indication that the militaristic reputation of the new Germany’s northernmost region was still relevant, and the second one (“war is the national industry of Prussia”) is explicitly racist, with its German “hun” looming very large indeed.

The “Prussian Octopus” (1915; University of Toronto) and “La Guerre est l’industrie Nationale de la Prusse” (1917; Library of Congress).

There’s an easy transition to the propaganda maps of World War II,when both sides used octopuses to put forward their points of view. Hitler is obviously an easy octopus, as the title and cover of a prescient book published by a correspondent for the Atlantic Monthly in 1938–just before the Germans moved into Czechoslovakia–boldly asserted. Henry C. Wolfe was trying to wake up the west and he used the octopus to do it.

Once the war began, the very clever German propaganda machine issued an anti-British poster from the perspective of France, which they had occupied: Winston Churchill as octopus reaches out toward French colonial possessions in Africa and the Middle East, echoing the imperial competition of the later nineteenth century. The bleeding tentacles–the amputations– indicate that Germany is preventing an English takeover of the French empire, even as it occupies France itself!

“Have Faith”: German anti-British propaganda poster, Victoria & Albert Museum, London.

As you can imagine, when the real war is over and the Cold War commences, the octopus continues to flourish as a symbol of rampant (anti-American) capitalism and rampant (anti-Soviet) communism, as well as rampant consumerism, evangelical Christianity and Islam, and a host of other perceived threats. However, cephapodal cartography is not subtle, and I think it lost much of its resonance in the later twentieth-century world, after the very literal 1950s.

British Economic League anti-Communist pamphlet, Archives of the Trades Union Congress and Warwick University Cold War Archive.

Now octopuses are rather whimsical, rather than threatening. I superimposed one on a cropped frame of a beautiful 1771 map of Salem and its vicinity and found it charming rather than ominous: what would they have been afraid of then? Definitely redcoats and tax collectors. What are we afraid of now?

January 22nd, 2013 at 11:42 am

A proper Napoleon depiction was already used by Matt Taibbi in Rollingstone Magazine in his description of Goldman Sachs as “a giant, vampire squid wrapped on the face of humanity.” I think that would have worked well for Napoleon and also satisfied the mollusk connection at least.

January 22nd, 2013 at 1:41 pm

Perfect, Richard, thanks!

January 22nd, 2013 at 12:13 pm

The interesting thing is that octopuses (octopi?), as I understand it, are pretty timid creatures. I suppose the idea of an octopus or squid grabbing a sailing ship with its tentacles and sinking it is a fear that goes back hundreds, if not thousands, of years, however.

And they really do work quite well for representing something insidious that is trying to take over everything. Of course, Frank Norris went with “The Octopus” as the title for his 1901 novel about corrupt railroads trying to steal land from hard-working farmers.

January 22nd, 2013 at 1:42 pm

I’m going with octopuses (as it is not a Latin word), and I totally forgot about that book! Thank you so much for mentioning it; the reference fits in perfectly.

January 24th, 2013 at 1:11 pm

Wonderful post – a richly deserved Freshly Pressed – congrats! I’ll bet you’re a great teacher.

Hmmm – what would we be afraid of today? I think that depends very much on where you live and what you believe. “Creeping liberalism” comes to mind as a term intended to evoke the octopus in our subconscious. Others might imagine the cloth of an Islamic turban strangling the world. On the other side of the coin, how about a spiderweb of American drone targets and deaths?

I, personally, fear hatred and the “otherness” that keeps us from being able to understand one another and work together to better the world. What’s a symbol for that?

Thanks for the food for thought. Congrats again.

January 24th, 2013 at 6:52 pm

And thank you for your thoughtful response, Melanie.

January 24th, 2013 at 2:11 pm

Reblogged this on misentopop.

January 24th, 2013 at 3:25 pm

This is cool! I’ve only seen these kinds of maps on occasion, but I had no idea there are so many!

Cheers,

Courtney Hosny

January 24th, 2013 at 3:35 pm

What a wonderful article and those pictures are stunning. I would love to have one of those pictures printed out and put on my wall! 🙂

January 24th, 2013 at 3:48 pm

I didn’t realize there were that many either. Might make a good special topics course 🙂

January 24th, 2013 at 4:01 pm

Reblogged this on Urbannight's Blog and commented:

Just because they are cool and someone out there may need a chthulu fix.

January 24th, 2013 at 4:07 pm

Wonderful images! And rather funny given the natural history of octopuses: most are extremely short-lived, and their tentacles are actually quite delicate, breaking off (like a lizard’s tail) if pulled too hard. Although I suppose you could argue that they’re a fairly good analogy for an overreaching empire….

January 24th, 2013 at 4:47 pm

Reblogged this on Le cul entre les deux chaises and commented:

This post has so many things I love: maps! history! Europe! countries being total assholes to other countries! The only thing it’s missing is condiments (everyone knows you should serve octopus with a sauce).

January 24th, 2013 at 4:55 pm

Brilliant! I watched a documentary a while ago on maps and I remember those old representations of Russia as the big grey octopus being particularly stunning! Thanks for sharing 🙂

Rohan.

January 24th, 2013 at 5:11 pm

I’ve heard the reference, regarding octopi, in this way but I never have seen it illustrated on a map. Great and informative post; thank you.

January 24th, 2013 at 6:41 pm

Good post! I am following you now! My name is Carlos, if you ever want to know about Ocean Paddling follow us back. Regards!

January 24th, 2013 at 7:06 pm

Love thos old maps!!! Thanks for this.

S. Thomas Summers

Author of Private Hercules McGraw: Poems of the American Civil War

January 24th, 2013 at 7:11 pm

Very cool and rare photos. Thanks for post….www.ottomandandy.com

January 24th, 2013 at 7:40 pm

Thank you for sharing article and photos

January 24th, 2013 at 8:01 pm

How can you not see the Cthulu connection?! We’re all doomed! 🙂

January 24th, 2013 at 8:05 pm

Great post. I’m keen on history and had seen a few of those maps previously (such great pieces, semi-amusing yet serious & the octopus is such a apt & powerful image) But I’d certainly never seen so many gathered together. Loved the commentary & history also. Thank you for sharing. Arran.

January 24th, 2013 at 8:12 pm

Reblogged this on Agus MASRIANTO's Blog and commented:

This is mindmapping method

January 24th, 2013 at 9:48 pm

These are fantastic!

January 24th, 2013 at 10:38 pm

We need an Internet octopus map (or maybe octopi: Microsoft, Google, Apple, etc.). And could an octopus’s tentacles bear the symbols of drones?

It doesn’t feature an octopus, but one of my favorite uses of animals for nations is “The Harmless Necessary Cat,” which is most of the way down the page at this URL: http://mideastcartoonhistory.com/Prologue4.html

January 24th, 2013 at 11:15 pm

These are phenomenal! I can’t believe the book I once read on the history of comic strips and political cartoons failed to mention them.

January 25th, 2013 at 1:28 am

Cool maps. The octopus does double duty as showing a invasive or (undesirably) influential presence to its neighbors, even as its size conveys a position of power. Much better than a “sphere of influence” and a legend with gradient colors.

January 25th, 2013 at 4:05 am

Wow. You do have an impressive photo collection yourself! Congrats for a well deserved FP!

January 25th, 2013 at 4:41 am

Brilliant!

January 25th, 2013 at 8:54 am

Interesting post! Marleen Smit, author of the blog Maps and the City, has also done a lot of work with these map cartoons. https://www.facebook.com/MapsandtheCity

January 25th, 2013 at 12:58 pm

I love maps/political cartoons like this. I’ve also seen plenty of anti-Semitic cartoons that use Satanic looking octopuses.

January 25th, 2013 at 1:12 pm

I saw several as well (and some anti-Mormon maps) but decided not to include them. Obviously the poor octopus was used in many (mostly negative!) ways.

January 25th, 2013 at 2:55 pm

This was unusual and enjoyable – thank you

January 25th, 2013 at 3:21 pm

That’s a really interesting and useful post. Thank you!

January 25th, 2013 at 8:18 pm

[…] Teaching With Tentacles: … […]

January 25th, 2013 at 10:03 pm

Great post, what a neat theme to discover

January 25th, 2013 at 10:43 pm

very nice post..

BTW octopus sushi seems delicious…

January 26th, 2013 at 3:09 am

Great post, extraordinary post in truth.

Did you know that as a shamanic totum octopus is considered reflective of the mystic center and the unfolding of creation i.e. octopus holds the potential to change history.

Which is very useful when your engaged in the business of empire building. For not only does this totum have the power to change ones own history but also change the history of others too.

January 26th, 2013 at 3:22 am

Reblogged this on Bored American Tribune. and commented:

— J.W.

January 26th, 2013 at 3:34 pm

Fantastic images – and a wonderful insight into both the history of 1870s Europe in its age of military nationalism (the ‘Reich’ mentality that drove Germany for 80 years), and the way people perceived it at the time. And what a perception – each power viewing the other as a tentacular threat to their own interests, a de-humanised menace. Instantly we understand the way they ended up first socialising the superficial artifice of the military – sailor suits for boys, the ‘rock star’ status attributed to British admirals in the 1890s and so forth – and then falling helter-skelter into the First World War. A wonderful post that sums up so much about the realities of that age – and thank you for finding and sharing!

January 26th, 2013 at 5:48 pm

Thanks for your thoughtful response, Matthew.

January 27th, 2013 at 2:07 am

What a fabulous post. I love history, maps and propaganda posters and sometimes blog about them myself but had never seen an octopus one before. A really interesting and fun piece.

January 28th, 2013 at 5:57 am

Nice article, it seems that the “Octopus” meme is a very useful one.

January 28th, 2013 at 9:13 pm

Octopus map is indeed an effective way and the best way to teach world history in order to catch students attention. A very informative post!

January 28th, 2013 at 10:18 pm

Reblogged this on terugnaardetuin.tk ////// net als contractie van een kloppend hart ///// buiten als vanbinnen.

January 29th, 2013 at 12:56 pm

Where’s the octopus depicting America’s reach cross the globe today? After displaying history, and discussing the results that befell each of those nations, I think a map that draws the parallels between the past and our own nations warmongering reach across the globe would teach volumes.

January 29th, 2013 at 1:00 pm

Well, there were plenty to choose from, but they didn’t really meet the artistic standards of the earlier maps–they were more sketches than true designs.

January 29th, 2013 at 2:59 pm

Greatly chosen subject for a post! And done very well. Love the octopi maps! :)))

January 30th, 2013 at 10:53 am

what a great post!

February 1st, 2013 at 3:57 am

Great subject and very informative. I love all your beautiful maps and the progression of the designs that reflect art styles of the various cultures and events in history. Cheers!

February 1st, 2013 at 12:01 pm

BRILLIANT! Thank you for collecting all of these together and I appreciate your commentary. Way to make some excellent connections. Plus, well, I love octopi and editorial cartoons so I couldn’t resist. 🙂

February 3rd, 2013 at 12:03 am

Poor old octopuses – I’m sure they’re not really greedy, aggressive creatures hell-bent on world domination. They certainly work as a convincing visual metaphor though… for imperialism… or indeed Starbucks.

February 3rd, 2013 at 2:11 am

What a beautifully inspiring blog. A creative teacher is someone we remember most of our lives. What a legacy.

February 7th, 2013 at 3:04 pm

[…] to have one, every major power gets their turn at being represented by an evil octopus. Donna Seger Teaching with tentacles – she’s contemplating teaching a whole semester of world history through octopus […]

February 15th, 2013 at 9:08 am

I majored in European History in college, but this is a whole new way to see it. I wish my professors used some of these maps, they are so much more fun than your standard-issue school maps nobody finds very interesting 😉

Cool blog!

February 16th, 2013 at 11:05 am

Such a breath of fresh air. It’s startling how modern historians are lauded for compiling the most number of sequential facts. No wonder their books only sell to other historians and universities. What percentage of the world is able to retain that much information? A picture is worth 1000 words. Rock on.

February 18th, 2013 at 2:17 pm

As a teacher and former history major, this is FUCKING brilliant.

April 20th, 2013 at 12:11 pm

[…] sobre mapas, no mercer la pena que me explaye en ello. (En caso de que os interese podéis mirar aquí, aquí, aquí y aquí) Ejemplos visuales […]

November 26th, 2013 at 10:50 pm

Reblogged this on Homie Williams. and commented:

— J.W.

August 25th, 2014 at 10:06 am

[…] Partizan He's actually serious Yeah I'm serious. They've been around for a very long time Teaching with Tentacles | streetsofsalem This is a very famous one… John Bull and Friends vs Russia Sign in or Register […]

March 6th, 2017 at 10:25 pm

[…] War Map For The Year 1877 Donna Seger at streetsofsalem posted a few years back about octopus propaganda maps from the 19th-20th […]

March 11th, 2017 at 12:12 am

[…] England as an Octopus […]

July 2nd, 2018 at 8:12 am

[…] Americans portrayed the Japanese as rodents. The Japanese and the British drew cartoons of the Russian octopus stretching its tentacles across Asia. The Germans painted the picture of a British spider weaving […]

January 10th, 2019 at 4:00 am

[…] animals. Often, the chosen animal is vermin, such as cockroaches or rodents. Sometimes they are an octopus or a spider, stretching their tendrils and tangled webs across the world. This is done because most […]

January 31st, 2022 at 3:30 pm

[…] Anonymous American cartoon, 1882, for more octopus maps, see here; R: Joseph Conrad’s searing 1899 depiction of colonial […]