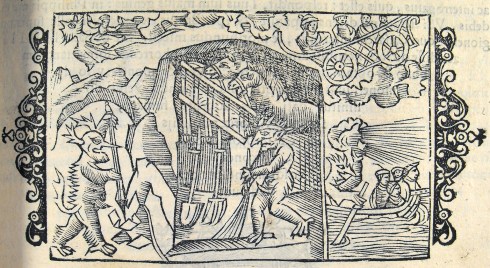

The witch trials in early modern Europe, which resulted in the execution of between 40,000 and 60,000 people and targeted double that figure, focused on devil worship more than anything else, but maleficia (harmful magic) was often the trigger, and the evidence, for the identification of conspiratorial witchcraft. And of the various types of harm that witches were accused of committing, nothing was more generic, and more harmful, than weather witchcraft. One of the earliest printed depiction of witches makes the connection concrete: two hag witches are literally whipping up a storm in a cauldron.

Ulrich Molitor, (fl. 1470-1501), De lamiis et phitonicis mulieribus (Cologne, 1500).

Even if we can’t understand the fear of witchcraft in our rational era, we can understand the threat of weather witchcraft to a civilization that depended on the climate for food, and life. Our supposed mastery of nature leaves us a lot less vulnerable–at least we like to think so. But in the premodern past, a storm could bring hunger at best and starvation at worst. The source of evil is always a problem in Christianity, as it is in every culture: why do bad things happen to good people? The devil and his witches–the servants of Satan–provided an accessible explanation. And for these reasons, I think that the earliest disseminated images of the witch focused on weather witchery: certainly those of the greatest printmakers of the day, Albrecht Dürer and his apprentice Hans Baldung (Grien) did: Dürer pictures a goat-riding witch attending by several putti and bringing forth rain, while Baldung’s more shapely weather witches are yielding their apple-capped flask to bring forth a storm with the aid of another demonic putto and of course, the demon-goat. This particular image is obviously a painting, but Baldung created several influential woodblock prints of witches depicted in an overtly sexual manner, intensifying interest in them even more in the early sixteenth century.

Albrecht Dürer, The Witch (1500-02), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Hans Baldung Grien, The Weather Witches (1523), oil on panel, Städel Museum, Frankfurt.

As I am writing this, I keep checking for updates on Hurricane Sandy, and I just read about the abandonment at sea of the Canadian replica tall ship HMS Bounty (made for the 1962 Marlon Brando film), and the loss of several members of her crew. This was the particular witchcraft fear in Scandinavian cultures: witches stirred up storms at sea and sank ships. You can see this fear illustrated in the Historia de Gentibus Septentrionalibus of Olaus Magnus (1555), a grand compendium of Nordic popular culture and folklore, as well as in King James I and VI’s pamphlet about the famous North Berwick trials: Newes from Scotland – declaring the damnable life and death of Dr. John Fian (1591). Upon his engagement to Anne of Denmark, James spent time in Scandinavia and became exposed to continental witchcraft beliefs: the stormy voyage he endured on his return trip home combined with his belief that as “God’s lieutenant” he was the target of demonic conspiracies inspired him to be a particularly zealous witch-hunter both in Scotland and England.

Magnus’s Historia and Newes from Scotland woodcuts: Ferguson Collection, University of Glasgow Library Special Collections.

The contemporary record of one of the largest witch hunts in European history, occurring at Trier in western Germany from 1581 to 1593 and resulting in the death of over 360 people, is illustrated with a composite picture of all the activities of witches, including storm-making with a broomstick. In central Europe, hail seems to have been the most commonly-identified form of magical weather and could definitely provoke accusations. Hail does seem kind of magical, if you think about it.

Title page of Peter Binsfeld, Tractatus de confessionibus maleficorum et sagarum (1592).

You can see from the title page of one of the pamphlets reporting the Lancashire (Pendle) trials of 1612, the largest trials in England, that weather witching was one of the accusations, along with riding the wind. I am not certain if any specific weather charges were leveled at the accused witches here in Salem, although I do know that the intense cold, and the hardship it brought to this community, has been considered among several contributing factors in the background of the 1692 trials. This follows the European historiography, which has been considering the impact of the “Little Ice Age” on witch-hunting for some time.

A goat-riding witch brings down a storm: from the Compendium Maleficarum of Francesco Maria Guazzo (1628).

October 30th, 2012 at 7:50 am

I knew that the european witch hunts were widespread but had no idea of the scope.. this kind of history is well hidden from high school students.. wonderful images. I hope this naturally occurring storm will soon ride its own nasty self right out. c

December 24th, 2012 at 11:49 am

Wonderful post, Donna. You do a great job of explaining how ‘natural’ (to us) events could be interpreted as magical in a time before scientific meterology or medicine.

I’m not sure I agree with your aside at the start though: in England at least most witch trails were very much focused on ‘harmful magic’ rather than ‘devil worship’. My impression is that the latter was a bit of a top-down imposition from elite demonologists – the average villager was much more worried about witches causing hailstorms or, as I discuss in a post on ‘The Many-Headed Monster’, causing cattle to fall sick.

http://manyheadedmonster.wordpress.com/2012/12/24/a-seventeenth-century-christmas-mince-pies-jollity-and-witchcraft/