Happy New Year! And my very best wishes to all for a better year than last! I’m a little bleary-eyed, having worked very hard over the holidays on grading and my forthcoming book, which is due at the publisher on March 1. And I’ve got to prep for next semester, which will include a brand new course on English legal history of all topics (yawn: a requirement for our department’s pre-legal concentration). So my posts are going to be a bit sporadic over the next few months but I did want to ring in the New Year with a post and give you all the heads up. Even after ten years, there’s still quite a few Salem topics I want to take on, and I’m hoping, like many of you I am sure, to travel at some point in 2021 so I should have some interesting posts after my big delivery date!

Normally I’m all about books on the blog this time of year: end-of-year best booklists, books I’m looking forward to reading, books for my courses. I’m so focused on my own book this year that I can’t really think about other people’s books during this particular January, except for very specialized academic books which I must include in my bibliography. Books for me are not just things to read however, they are objects which I like to have around, to dip into and just to look at. I love everything about book-objects: fonts, paper, cover design, illustrations, formats, colors. And my favorite books of all are Penguins: plain old orange-and-white paperbacks with yellowed pages and very pretty clothbound classics of more recent vintage and everything in between. I have evolving favorite series, and when I’m focused on a particular series I want to collect every volume possible: a couple years ago it was mid-century King Penguins and I remain very fond of them. People have given me gifts so I have quite a few now: I received “Compliments of the Season” this very Christmas.

My most recent Penguin obsession, however, is the Drop Caps series, a colorful collection of twenty-six classic hardbound books designed by Jessica Hische, lettering artist extraordinaire. I saw one in a bookshop this summer and suddenly had to have all of them, and I have collected quite a few in the past six months or so. They are very object-like: you can shelve them and stack them in all sorts of interesting combinations. This makes them the perfect Penguins for me now, as I don’t actually have time to read them. But I will soon.

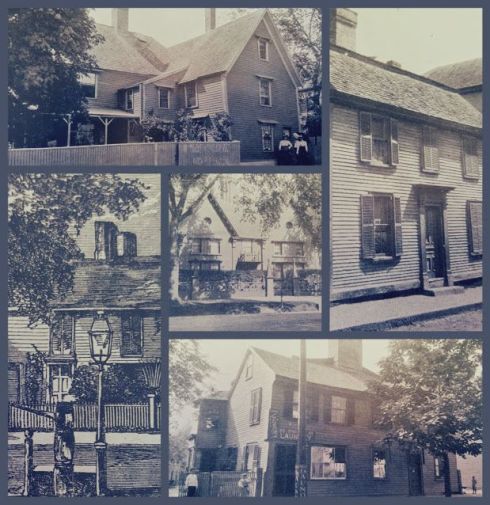

One of Darcy’s last photographs, Trinity, Tuck.

One of Darcy’s last photographs, Trinity, Tuck.