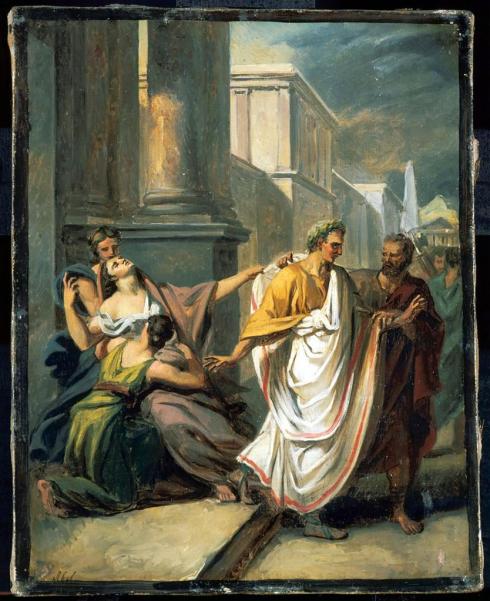

My garden looks like it might have survived our harsh winter so I’m starting to turn my thoughts outward–slowly, and in a rather detached manner. There’s still quite a bit to do inside as the end-of-semester end game is pretty busy, and once I get fixated on the garden I become less productive in the interior realm! The other day I was showing my students a beautiful painting of a famous Royalist family, the Capels, whose prominent garden is featured in the background. While my eyes were lingering on the garden, their questions were about the children in the foreground: what were their fates after their father followed King Charles I to the execution block in 1649? I couldn’t account for every Capel child in the picture at the time (now I can) but I could relay the horticultural history of the two Capel girls on the right, Elizabeth and Mary. I don’t think this kind of information was what my students were looking for, but they were quite polite about it.

Cornelius Johnson, The Capel Family, c. 1640, National Portrait Gallery, London; Peter Lely, Mary Capel, later Duchess of Beaufort, and her sister Elizabeth, Countess of Carnarvon, c. 1658, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

As you can see in both paintings, the youngest Capel sister, Elizabeth (who is on the left of her elder sister Mary in the Johnson portrait and the right in the Lely) is associated with flowers in both her childhood and her adulthood. She is extending a rose to her baby brother Henry above, and below she holds one of her own flower paintings–a noted personal preoccupation during her relatively short life (1633-1678). Around 1653 she married Charles Dormer, the 2nd Earl of Carnarvon, with whom she had four children. During their marriage she maintained the Dormer residence at Ascott House in Buckinghamshire, and continued to explore her interest in flowers through both gardening and painting. One of her botanical compositions, a Dutch-inspired still life, is in the Royal Collection. Mary Capel, later Seymour, then Somerset and the first Duchess of Beaufort (1630-1715), moved well beyond her sister’s aesthetic interest in plants into the realm of scientific botany, becoming an avid collector and cataloger of the vast collection of worldly plants she assembled for the Beaufort gardens and conservatories at Badminton House in Gloucestershire and Beaufort House in Chelsea. She commissioned both a 12-volume Hortus Siccus, comprised of dried specimens of her plants, many “pressed by the Duchess herself”, and a two-volume florilegium to document her collection, ensuring her reputation in the long line of notable British plantswomen.

Vase of Flowers by Elizabeth, the Countess of Carnarvon, 1662, Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2014; Specimens from the Duchess of Beaufort’s Hortus Siccus, Natural History Museum, London.