As I am typing this, beside me is a little hand-bound and -printed pamphlet of verse, what one might call a chapbook, dating from 1852: it is one of many similar publications produced by the Reverend William “Billy” Cook (1807-1876) in the middle of the nineteenth century and sold to family and friends. The son of a prosperous ship captain, Cook spent his entire life in Salem except for stints at Phillips Academy in Andover and Yale University, from which he failed to graduate because of illness–both physical (typhus) and mental: his sole biographer, Lawrence Jenkins, writes in 1924 that “unkind Nature” had failed to outfit this “gentle soul” with a “complete and well-balanced headpiece”. After his return to Salem, Cook studied for the ministry but never made it beyond the level of Deacon: nevertheless he and everyone else seems to have referred to him as “Reverend”. To make ends meet (as the captain’s money seems to have run out), Cook tutored private students in Latin, Greek and mathematics and began writing and sketching. He maintained what is referred to as an “art gallery” in his home on Charter Street and included woodblock illustrations in all of his publications. These woodblocks are quite primitive, nevertheless they highlight the fact that Salem was Cook’s entire world as numerous street scenes and buildings are intermingled among his verse whether they have anything to do with Salem or not. According to Jenkins, the woodblocks were carved from maple or birch wood by Cook with a jack-knife, and touched up with lead pencil or paint after they were printed–one page at a time–on a hand-press that he had built himself. This rather rudimentary process is revealed by the folk nature of the prints, but I think it also renders them a bit more timeless, and charming.

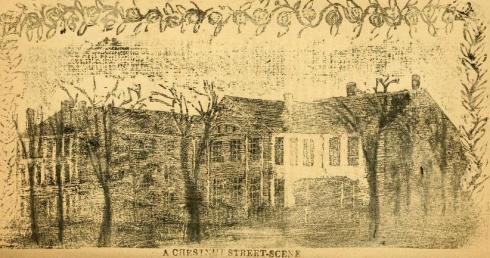

I wish I knew more about William Cook. Jenkins’ article definitely paints him as a rather eccentric figure, but isn’t he in a similar situation as his contemporary Nathaniel Hawthorne? The old Salem money had run out for both of them, and they had to depend on the their well-placed friends and ink-stained hands to provide for themselves. And they were both so so shaped by Salem. (I think the similarities must end here). The poem that illustrates Cook’s life the best for me is his “Chestnut Street”: not only did he include the names of all the contemporary residents of the street but also accompanying illustrations of nearly every building by my estimation (including the McIntire South Church). He had to: these were his patrons. So here we have quite a different Chestnut Street than that portrayed later in the photographs of Frank Cousins or the etchings of Samuel Chamberlain. Cook’s style emphasized the elemental fundamentals–chimneys and windows–and all those top-heavy, twisting trees–the lost elms of Chestnut Street, I believe.

All illustrations from The Euclea collection of Cook’s poetry, 1852; For more on Cook see the only source: Lawrence Jenkins, William Cook of Salem, Mass.: Preacher, Poet, Artist and Publisher,” in the Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society, New Series, Vol. 34, April 9, 1924-October 15, 1924.

Leave a Reply