Apparently our British cousins across the Atlantic are not entirely pleased with the official royal wedding china issued in advance of the upcoming nuptials of Prince William and Kate Middleton, provoking the production of unofficial alternatives like the plate below, one of several offered by London-based KK Outlet:

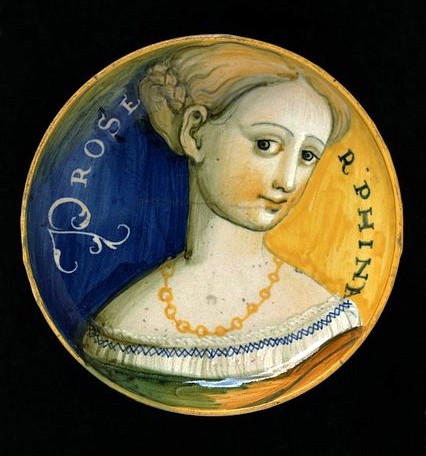

This got me thinking about souvenir or commemorative china in general, and plates in particular. Actually I was inspired by an earlier post on Frank Cousins and his wares to look closer at Salem souvenir plates, but it seems sensible to take a longer (and broader) view. As they are with so many advertising innovations, I assumed that the Victorians were the pioneering producers of commemorative china, but if we examine the genre in terms of its most basic purpose—remembrance—we can go back further, to at least the Renaissance. Italian Renaissance maiolica potters regularly produced domestic pottery to commemorate family events, generally betrothals and births, as these two examples (Urbino, 1530 & 1540) from the huge majolica collection at the Victoria & Albert Museum illustrate:

Moving forward several centuries we have two amazing examples (also from the V & A) of European commemorative china commissioned from China, reminders that Europeans had their “China Trade” well before Salem merchants established their Asian trading connections. Both plates are from the mid-eighteenth century; the first commemorates the arrival of a Dutch East India Company ship in Chinese waters, the second marks the Jacobite Uprising in Scotland in 1745 (Strange Kilts! Actually the wearing of all tartan kilts was banned by the British government—until 1782—in retaliation for this rebellion).

As we move into the nineteenth century, souvenir china is transformed from bespoke to retail trade because of changing conditions in both supply and demand, converging in the foundation of a “mass market”. Still mining the vast collection of the Victoria & Albert, I’ve come up with several Victorian and Edwardian souvenir plates, capturing such iconic British images as the great Crystal Palace Exhibition of 1851, Queen Victoria’s Jubilee Year, and the Bard.

This last Shakespeare plate dates from 1904, and is similar in color, style, period and origin to the Salem souvenir plates below, which represent a very small sample of English plates produced for the American market prior to World War One. The Boston firm Jones, McDuffee & Stratton had a virtual monopoly on importing the popular Wedgwood blue-and-white transferware decorated with “historic” American scenes (listing 78 designs in their 1910 catalogue and as many as 300 patterns overall), and so their Salem competitor Daniel Low & Company turned to smaller Staffordshire potteries for the production of their designs. With the earlier success of their witch spoon, it was only natural that they would now offer “Salem Witch” plates.

Fortunately there is another Salem image that has appeared in ceramic form over the past two centuries: that of the famous Salem East Indiaman Friendship, which made 17 global voyages before its capture by the British in the War of 1812. Just a few years later (1820), the beautiful Chinese Export Friendship platter below might have been commissioned by some sentimental Salem merchant, and just last year, it was auctioned off by Sotheby’s with an estimate of $6000-$8000 (and a realized price of over $53,000!) It contrasts quite sharply with the last plate, from a line produced by Wedgwood around 1977, which is widely available on the second-hand collectibles market for around $40.

January 27th, 2011 at 9:07 am

You keep writing about all my favorite stuff! Don’t forget that even Old Spice got into the act, using the Friendship on their shaving mugs…if they’re not still issuing these, they only stopped fairly recently. They’re very available in antique shops.

Another item allied to these commemorative plates and other items is Victorian fairings. These were made in Germany, as cheap souvenir pieces. Like the cobalt blue china souvenir pieces and the postcards of American scenes from Germany, these stopped with World War II. Apparently the German glass Christmas ornament manufacture resumed after the Second Wrold War, but apparently tastes had changed and the “fairings” and the Cobalt blues were not revived.